Spanish Flu: Providing Care During a Pandemic

Caring for the poor at a time when many diseases could spread rapidly and turn into epidemics carried was highly risky for nuns. Tuberculosis, for example, was one of the most devastating infections at the turn of the 20th century. Self-sacrifice took on a whole new meaning for nuns who, while trying to relieve sick people’s suffering, sometimes lost their own lives. At the Hôtel-Dieu de Quebec alone, there were three nuns in 1896, six in 1900 and two in 1901 to succumb to the disease. However, the influenza of 1918, known as “Spanish Flu,” took the Augustinians of Québec City by surprise.

© Archives du Monastère des Augustines

Fonds du Monastère des Augustines de l’Hôtel-Dieu de Québec.

The Spanish Flu

In 1918, the last major epidemic, the Spanish Flu, wreaked havoc across Québec and Canada. There were 50,000 deaths related to this pandemic in the country, while this number rose to about 200 million worldwide[1]. The second wave of the Spanish flu hit Québec City in mid-October 1918, taking an average of 40 people a day during its first week. Theaters, schools, taverns and even churches were closed for three weeks. Business operated on a reduced schedule.

The Augustinians managed to survive a good part of the crisis, despite being ignorant of the causes of and remedies against the disease. The economic crisis following the First World War was also felt: there were not enough means to provide optimal to everyone. The various vaccines, remedies and isolation techniques (quarantine) were of little or no effect. The three monastery-hospitals were mobilized to fight this epidemic, but soon, these hospitals’ premises were no longer adequate.

© Archives du Monastère des Augustines

Fonds du Monastère des Augustines de l’Hôtel-Dieu de Québec.

The nuns were not spared

During this episode, 58 of the 138 Augustinians in the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec suffered from this disease. Only one died, but three more

Augustinians weakened by the virus died later from this infection; they contracted tuberculosis that was fatal to them.

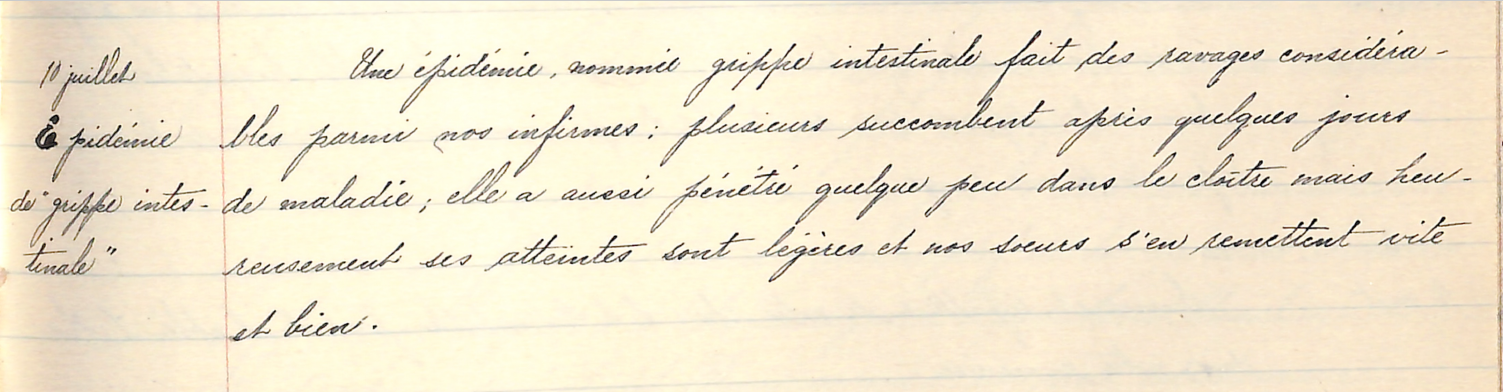

As for the Hôtel-Dieu de Quebec, 28 “novice and young professed” Augustinians fell ill, without any succumbing to the disease. The annals describe an “epidemic called intestinal flu [which] has considerably ravaged the weak.”

At the Hôtel-Dieu du Sacré-Cœur, the disease was particularly aggressive. At the height of the crisis, there were reports of “nuns who fell ill, several at a time; the infirmary was not enough, the chapter house and then the community room were added.” In this monastery with about 80 nuns, three novices and young professed souls died in the following weeks.

© Archives du Monastère des Augustines

Fonds du Monastère des Augustines de l’Hôpital général de Québec.

Selflessness

The nuns fatally affected by the disease did not question the usefulness of their role and mission. This is how Sister Saint-Anselme, a few days before her imminent death, was grateful to die in the service of the poor. She expressed this as follows: “I make this sacrifice and above all, I sacrifice my life with all of my heart so that all others can be spared.”

For her part, Sister Sainte-Monique, also condemned by the disease, displayed, it is said, an “attitude [which] was that of all her religious life. What peace, what a sweet smile, what patience!” It is perhaps in this final acceptance that the extent of self-sacrifice on the part of the Augustinians manifested itself in the most concrete way.

© Archives du Monastère des Augustines

Fonds du Monastère des Augustines de l’Hôtel-Dieu de Québec.

Improvements in sight

These times of great stress ultimately contributed to a certain improvement in the living conditions for hospital patients. The night watch, responsible for caring for the sick during the night, had only a slight respite at the very beginning of the First World War (they could get up at 5:10 a.m. instead of 4:00 a.m. like the others). In 1919, the council pushed this time back to around 10:30 a.m. – 11:00 a.m. On Sundays, they could even wake up at noon. Ten years later, permanent night teams were established to avoid the inconvenience of changing the schedule. It seems the importance of a restful sleep was better understood!

References

Becker Annette. “L’histoire religieuse de la guerre 1914-1918”. In: Revue d’histoire de l’Église de France, tome 86, n°217, 2000. Un siècle d’histoire du christianisme en France. p. 539-549.

Jean-Charles Fortin. Les soins de santé et l’assistance publique avant 1960, Chaire Fernand-Dumont sur la culture, September 24, 2003.

François Rousseau, La croix et le scalpel : Histoire des Augustines et de l’Hôtel-Dieu de Québec, tome II: 1892-1989, Québec, Les Éditions du Septentrion, 1994, p.280-282.

Monastère des Augustines archives, Lettre annuelle de l’Hôtel-Dieu-du-Précieux-Sang, Sœur Marie du Calvaire, December 23, 1918

Monastère des Augustines archives, Lettre annuelle de l’Hôpital Général de Québec, Sœur Saint-François d’Assise, December 16, 1918

Monastère des Augustines archives, Lettre annuelle de l’Hôtel-Dieu-du-Sacré-Cœur-de-Jésus, Sœur Sainte-Gertrude, December 26, 1918

Monastère des Augustines archives, Annales de l’Hôpital Général de Québec 1915-1926, p. 182-183

[1] Research sometimes speaks of between 5 and 100 million deaths, but new data would increase the number to 200 million. (Editor’s Note)